What is CONIMCHH?

CONIMCHH - the Consejo Nacional Indigena Maya Ch'ortí de Honduras - is a private nonprofit organization in Honduras that facilitates the comprehensive development of its affiliated communities, including efforts promoting economic development, the recovery of ancestral lands, cultural recognition and general education.

Mission

CONIMCHH strives to

- advance the comprehensive development of our affiliated communities through the defense of our inalienable rights;

- form male and female leaders with a strong spirit of service, responsibility and political, technical, and managerial capacity

- collaborate in search of solutions that enhance the recovery of the indigenous cultural identity; and

- economically and sustainably develop our recovered lands to reproduce a quality of life in harmony with our worldview.

Vision

- COMNICHH aims to be a strong indigenous organization, with a fully democratic structure and capable and conscientious leadership that facilitates economic, social, cultural, and political development of the Ch’orti’ Maya community in harmony with the environment and the Mayan worldview.

- Through strategic planning, the systematic payment of the membership dues, and the efficient use of funds and resources, we plan to achieve the technical training to introduce our goals of sustainable development to all of the necessary program areas for the communities to reach financial sustainability and the quality of the life the community members deserve, where an open community and a duty to human service prevail.

Organization

CONIMCHH is organized into a number of smaller groups, representing both regional communities and special interest projects.

History

The Founding of CONIMCHH

Agrarian Reform and Growth (1971-1979)

This was a time of agrarian reform and the growth of peasant organizations in areas such as the National Center of Rural Workers (CNTC) and the National Association of Honduran Peasants (ANACH). During this time, the government appropriated the first lands for Ch’orti’s in the communities of Carrizalón, Choncó, and Tapesco.

An Academic Recognition of the Ch’orti’ (1982-1987)

Professors Lázaro Flores and Gerardo Velásquez (from the Honduran National University [UNAH] and the National Pedagogical University [UPN]) began visiting the Ch’orti’ communities. They conducted an ethnographic study, which resulted in a book about identity. They also conducted a census and a registration of the indigenous Ch’orti’ Maya population.

ILO Convenio 169 (1989)

In 1989, an important event for the indigenous community occurred with the signing of the International Labor Organization (ILO) Convention 169 on Indigenous and Tribal Peoples in Independent Nations. This agreement awakened the indigenous community by restoring their rights. By 1991, various Ch’orti’s were assassinated for reclaiming their inalienable rights.

The Beginning of the Fight (1994-1996)

In 1994, ILO Convention 169 began to be recognized in the communities, and in April of that year, the Christian Organization for Development of Honduras made sure that the convention was being enforced in the Ch’orti’ towns. Honduras ratified the Convention on May 10, 1994. The provisional National Indigenous Ch’orti’ Council of Honduras (CONIMCHH) was organized in Santa Rosa de Copán on November 18-19, naming María de Jesús Interiano of Carrizalón, Copán, as the first Senior Counselor. They also selected the first rural indigenous assembly from the communities of Chilar, San Francisco, Estanzuelas, La Pintada, Barasqueadero, Rincón del Buey, Corralito, Carrizalito, Nueva Esperanza, and Llanetillos.

In 1995, a man of great courage and idealism, Cándido Amador, joined the cause. That same year CONIMCHH was incorporated with the Confederation of Autochthonous Peoples of Honduras (CONPAH).

In 1996, the official recognition of the community of Ch’orti’ Maya occurred, with an estimated population of 8,000 residents. They obtained the legal status as CONIMCHH with 19 affiliated communities.

Agrarian Reform and Growth (1971-1979)

This was a time of agrarian reform and the growth of peasant organizations in areas such as the National Center of Rural Workers (CNTC) and the National Association of Honduran Peasants (ANACH). During this time, the government appropriated the first lands for Ch’orti’s in the communities of Carrizalón, Choncó, and Tapesco.

An Academic Recognition of the Ch’orti’ (1982-1987)

Professors Lázaro Flores and Gerardo Velásquez (from the Honduran National University [UNAH] and the National Pedagogical University [UPN]) began visiting the Ch’orti’ communities. They conducted an ethnographic study, which resulted in a book about identity. They also conducted a census and a registration of the indigenous Ch’orti’ Maya population.

ILO Convenio 169 (1989)

In 1989, an important event for the indigenous community occurred with the signing of the International Labor Organization (ILO) Convention 169 on Indigenous and Tribal Peoples in Independent Nations. This agreement awakened the indigenous community by restoring their rights. By 1991, various Ch’orti’s were assassinated for reclaiming their inalienable rights.

The Beginning of the Fight (1994-1996)

In 1994, ILO Convention 169 began to be recognized in the communities, and in April of that year, the Christian Organization for Development of Honduras made sure that the convention was being enforced in the Ch’orti’ towns. Honduras ratified the Convention on May 10, 1994. The provisional National Indigenous Ch’orti’ Council of Honduras (CONIMCHH) was organized in Santa Rosa de Copán on November 18-19, naming María de Jesús Interiano of Carrizalón, Copán, as the first Senior Counselor. They also selected the first rural indigenous assembly from the communities of Chilar, San Francisco, Estanzuelas, La Pintada, Barasqueadero, Rincón del Buey, Corralito, Carrizalito, Nueva Esperanza, and Llanetillos.

In 1995, a man of great courage and idealism, Cándido Amador, joined the cause. That same year CONIMCHH was incorporated with the Confederation of Autochthonous Peoples of Honduras (CONPAH).

In 1996, the official recognition of the community of Ch’orti’ Maya occurred, with an estimated population of 8,000 residents. They obtained the legal status as CONIMCHH with 19 affiliated communities.

The Assassination of Cándido Amador and Efforts to Increase Pressure (1997-1998)

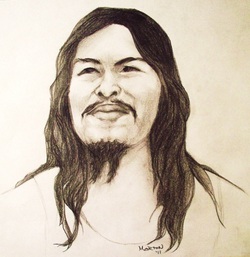

In 1997 Cándido Amador raised the flag and legal fight for the recovery of land, history, and culture of his people. On April 12 of that same year, he became a martyr for the cause. No less than 3,000 people from various indigenous communities (Tolupanes, Garífunas, and Lencas) attended his funeral. This event led to the Ladinos closing all their houses and businesses in the city of Copán Ruinas because they felt that the indigenous population was invading them. However, it was simply a demonstration of the unity and solidarity of the indigenous communities but the beginning of a great fight for the rights of the Ch’orti’ Maya culture.

Cándido Amador, having received death threats, had asked that in the event of his assassination his body be paraded throughout the entire town of Copán Ruinas. The masses complied, and his body was buried in the community of Rincón del Buey, Copán, in front of the school built by Japanese Embassy. Forty days later, his body was exhumed for an autopsy and was eventually buried in the community cemetery. The country of Guatemala requested his remains to place them next to those of conquest-era K’iche’ leader Tekun Uman, because to them Amador was the last great Ch’orti’ chief. Candido’s actions were not in vain, as soon thereafter the community rose up with even greater determination to continue the noble fight for indigenous rights.

On April 25, Ovidio Pérez, another valiant leader, was also assassinated. Four communities left the organization out of fear of landowner and military persecution of indigenous leaders. With fierce determination to recover our rights and emboldened by the pain of losing two of our leaders, on May 1 the Ch’orti’ Maya people led a pilgrimage to Tegucigalpa that was enjoined by entire COMPAH confederation.

The pilgrimage lasted 15 days and included a hunger strike on May 13. An agreement was signed with the state that day ceding 14,700 hectares to the Ch’orti’ Maya community. By December, the state purchased the first 350 hectares of mostly non-arable land for the Ch’orti’s. At the same time, development projects, such the construction in Rincón de Buey of a community municipal center, a school, and health center, and the CONIMCHH communications office were established.

While we began reaping the rewards of our fight, our organizational system was growing and the advancement towards our goals was accelerating. In August 1998, we made a second pilgrimage to Tegucigalpa and took over the Costa Rican embassy and carried out another hunger strike. Although we were violently removed by the state, we achieved additional concessions.

In protest of the slow pace of carrying out these agreements, on September 1we took over the Ceremonial Center of Copán Ruinas for the first time and blocked the international highway in Ocotepeque. The state responded with another violent ejection from the Center and the shooting of eight in Ocotepeque, resulting in one death. Subsequently, we took control of the National Agricultural Institute installations in Tegucigalpa, which resulted in the purchase of 1,715 hectares for the communities of Carrizalón, Boca del Monte, Chilar, Laguna, San Rafael, and Estanzuela. Another achievement that occurred in this period was the hiring of some Guatemalan teachers like Rigoberto López to teach the Ch’orti’ language and support the recovery of such customs and traditions as the Tzikin, rituals for bringing the rains, the corn harvest festival, and other Mayan ceremonies.